Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

How Concern understands extreme poverty shapes our work to end it.

Since 2020, the number of people living in extreme poverty has increased by more than half a million people, to over 648 million in 2023. Put another way, that means over 8% of the world's population lack basic assets or do not see a return on the assets they have and live under the poverty line of $2.15 per day.

For these 648 million people, these circumstances fuel a cycle of poverty that they're unlikely to break on their own. Many have inherited this cycle from their parents. Many will pass it on to their own children.

What does this mean for ending poverty? Here, we explain both what the cycle of poverty is, the two factors that fuel it, and how we at Concern address both in order to break the cycle.

The four types of poverty

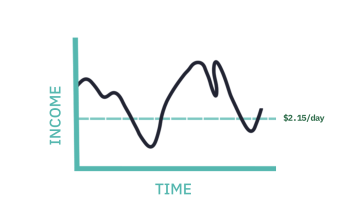

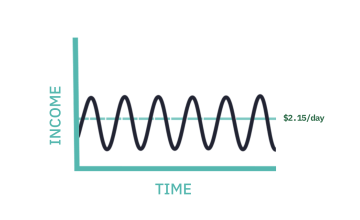

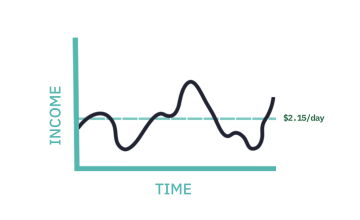

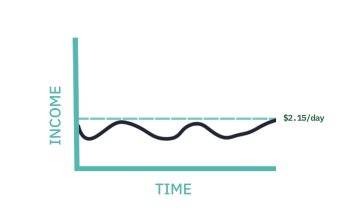

Poverty is dynamic, and numbers don’t tell the whole story. Often these numbers only give us a snapshot of people’s lives at one particular moment in time. Many families move in and out of poverty, experiencing it only occasionally or living on less than $2.15 a day for long stretches of time. Broadly, we can look at four different types of poverty:

1. Occasionally Poor

Occasional Poverty and Cyclical Poverty both represent transient poverty. People experiencing either of these types of poverty can expect to spend periods of time living above the poverty line. People experiencing Occasional Poverty are more likely to spend long stretches of time above the poverty line. However, an unexpected event, such as a fire or tsunami, can leave these groups more vulnerable.

Nearly half a million Filipinos face Occasional Poverty each year due to natural disaster. 2013’s Typhoon Haiyan hit the country especially hard: 70% of the country’s fishing community lost income. 65% lost key assets like boats. Jonel Meranar lost his home and his boat. As part of Concern’s Typhoon Haiyan response, he trained in boat repair and was hired at a boatyard in Concepcion. He also received his own boat. Within a year, he rebuilt his fishing business.

2. Cyclically Poor

What if the shocks that trigger periods of poverty for the Occasionally Poor are less severe but more consistent? This is the situation faced by millions of families who rely on agriculture for both their food and their livelihoods around the world. During peak periods, such as harvests, there is usually guaranteed income — either from working on someone else’s farm or from selling what’s harvested at the local market. Even without droughts or floods, hunger seasons between harvests can happen every year, resulting in Cyclical Poverty.

Malawi is 80% agrarian, which means that hunger seasons and poor harvests can leave families financially and nutritionally insecure. These low seasons can last for months, and are even more complicated if a natural disaster strikes — as Cyclone Idai did in 2019. Agnes Jack participated in Concern’s Graduation programme. She received a start-up grant and learned Climate Smart Agriculture techniques, which have improved her harvests and income, offsetting cyclical poverty.

3. Usually Poor

Usual Poverty is an inverse of Occasional Poverty. People experiencing Occasional Poverty are generally above the poverty line and only fall below due to an unexpected setback. People experiencing Usual Poverty are generally below the poverty line with the exception of an unanticipated windfall. This could be in the form of a good rain after a dry spell, or someone finding a short-term job that pulls their family above the poverty line for a few months.

In Niger, men often migrate abroad for work, sending money back home to support their families. However, these gains can be quickly lost if events like conflict or a pandemic prevent international travel, perpetuating a Usually Poor cycle. Balkissa Matsallabi’s husband was prevented from travelling to the Cote d’Ivoire. Programs like Concern’s Community Management of Acute Malnutrition can help to reduce the impact of these situations while families find more sustainable forms of income.

4. Always Poor

Those who are Always Poor, like people experiencing Usual Poverty, tend to be those who experience poverty over long periods of time — in many cases, over generations. Families experiencing Usual Poverty may either benefit from a good harvest or a rare period of high-income labour. However, families classified as Always Poor live consistently below the poverty line, even if there’s some fluctuation in their income following harvests or work opportunities.

In 2010 and 2011, the worst drought in 60 years gripped Somalia, triggering a famine that killed over 260,000. More than decade of poor rains has pushed 43% of the country’s population below the poverty line. Many families were still recovering from the 2010-11 drought when, in 2015, El Nino events once again led to failed rainy seasons. Somalia avoided a second famine in 2017, thanks to timely interventions and cash transfers. However, unprecedented drought in the Horn of Africa plus the economic impacts of the conflict in Ukraine leave many facing famine-like conditions in 2023.

What fuels the cycle of poverty?

As noted above, while the different types of poverty are centered on lack of assets or lack of a return on those assets, they also suggest different causes of poverty. The obstacles that keep a community in Lebanon in extreme poverty may be totally different than those keeping a community in Malawi in extreme poverty. That said, we can boil all of this down into two key dimensions that, when combined, equal poverty: marginalisation and risk.

Inequality

By inequality, we mean the systemic barriers that lead to groups of people without representation in their communities. In order for a community or country to work its way out of poverty, all groups must be involved in the decision-making process — especially when it comes to having a say in the things that determine your place in society.

All types of systemic barriers (including physical ability, religion, race, and caste) serve as compound interest against a marginalisation that already accrues most for those living in extreme poverty.

Gender discrimination is one of the biggest inequalities preventing the end of extreme poverty. This impact is felt in education: 650 million girls and women alive today were married before their 18th birthday. Usually, this means that they don’t finish school. Lenason Dinyero is a farmer from Malawi’s Nsanje district and the chairperson of his local school father’s group. They fight early and forced marriages, as well as other practices that prevent girls from their right to an education.

Risk

Risk is the combination of a group’s level of vulnerability and the hazards they face. The more vulnerable a group is — and the more hazards they face — the harder it is to break the cycle of poverty. As noted above, risk often takes the form of emergencies: natural disasters, outbreaks of disease, and conflict all hit more vulnerable groups harder.

This combination of hazard and vulnerability can fuel greater marginalisation, which in turn can leave marginalised groups more vulnerable and open to more hazards.

As newlyweds, Workitt Kassaw Ali and her husband Ketamaw faced a common challenge among young families in rural Ethiopia: not enough land. In the farming-focused Amhara region, this also means not enough income. The couple participated in Concern’s ReGRADE program, a variation on our Graduation model, and gained sound financial footing. When Workitt experienced a medical emergency, they were able to cover the medical costs—something they could not have done in the past. “I think it saved my life,” she says.

How do we break the cycle of poverty?

While each situation is different, Concern’s approach to breaking the cycle of poverty is focused on addressing marginalisation and risk. Looking at the waves that represent each type of poverty, our goal is to design interventions and programmes that straighten each of the waves out, and move the overall line above the poverty line.

Addressing inequality

It stands to reason that, if there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to poverty, there’s also no one-size-fits-all approach to ending it. Many communities have certain basic assets already. Many communities have a mix of people — some of whom have certain assets, and some who don’t.

To address inequality, we consider these different starting points, both acknowledging the different skills and means that people have and addressing the different barriers that people may face. For one family, building the foundation for success may be as simple as providing a start-up grant for them to launch a business. For another, we may need to go deeper with adult literacy courses, agriculture workshops, or addressing the cultural norms that discriminate against women in leadership roles.

As part of bringing the Graduation program to DRC, Concern requires that women play a full part in the decision-making process for their communities and works to find opportunities for them to take part in local leadership. Ngoy Francine is the treasurer of her local water committee in Tanganyika province. The committee charges a small fee for use to cover ongoing maintenance. “If people can’t afford to pay, there is no charge,” she says. “The community supports the most vulnerable.”

In the countries where Concern works, we prioritise understanding the ways that gender disparity presents at the national and local level, and how those inequalities affect participation in our programmes. We then look for ways to bring women not only into our programmes, but also into our staff and leadership in each country. With younger generations, we work to address gender imbalances and gender-based violence in the education system. With adults, we build support groups for both genders — ensuring that we're not only fixing the symptoms, but addressing the causes to develop lasting equity.

The more we can reduce inequality, the more we can work with communities to consistently earn more and stay above the international poverty line.

Addressing risk

The other lever we can turn in order to break the cycle of poverty is offsetting risk. The more a community is better prepared against hazards, and the more resilient it is against vulnerability, the less prone they are to risk. This also requires a tailored approach given that each situation is unique.

All Concern programmes incorporate some degree of disaster risk reduction as we work to offset the potential damage or harm caused by events ranging from climate disasters to conflict. Understanding how each individual hazard may affect a community, along with how they work together, is essential to having an effective response to risk. By focusing on specific vulnerabilities in specific situations, we can plan in advance to offset both catastrophic and everyday risks, creating a more stable and consistent quality of life for the people we serve.

The rainfall in Dar Sila, Chad, is unpredictable. This leads to seasonal food insecurity and malnutrition (among other risks). Concern has addressed this with Community Resilience to Acute Malnutrition. CRAM increases access to clean water and healthcare. Small business owner and mother Khamissa credits it with improving the community. “We like what we are doing and we hope to continue it as we are witnessing some type of change.”

The cycle of poverty: Who Concern works with (and why)

At Concern, our belief is that we must target our work so that it benefits primarily those living in extreme poverty. This means that we don’t always specifically target extremely poor people, but the extreme poor must be the ones who ultimately benefit from our work.

While we primarily work with the Always, Usually, and Cyclical Poor, we will also work with the Occasionally Poor when we believe that work will benefit those living in extreme poverty. This is especially true in times of natural and man-made disaster, such as the 2015 Nepal earthquake, the ongoing Syrian conflict, or the COVID-19 pandemic.

Turn your concern into action

Your donation to Concern means that over €0.93 of every €1 donated goes into our lifesaving projects in 25 countries around the world, helping us to reach tens of millions of people every year.